Apparently there are people who read this blog. Here's an article from the Milwaukee-Wisconsin Journal Sentinel dated February 1, 2010:

The Cell Peddlers: Dealing Hope to Desperate Families

Sorting out the sales pitch

The Internet has helped companies spread the word of 'miracle' recoveries, but families have to tread carefully

By Meg Kissinger of the Journal Sentinel

Posted: Feb. 1, 2010

Second of two parts

Megg Lasswell was writing a blog entry about her baby daughter's vision problems when an intriguing message popped on the screen.

Her daughter, GiGi, was born with optic nerve hypoplasia, making her able to see only blurry outlines and shapes. The message read:

"I can treat your child's ONH. You can look me up on the web if you like. My name is Kirshner Ross-Vaden and I work for a bio-tech company. Check out www.stemcellschina.com and www.beikebiotech.com. It is real. My email is kirshner@beikebiotech.com. I hope to hear from you. K"

Curious, Lasswell e-mailed Ross-Vaden for more details, but any hopes she had that the treatments would work faded. Over the course of the next several weeks, she learned that it would cost $30,000 or more for an unproven stem cell procedure with no reasonable hope of a cure.

Lasswell was livid.

"It's obvious now that these people don't care about our families," she said in her blog. "They are using a support group to offer people the world, or at least vision for their children. How cheap and disgusting is that?"

The company behind the unsolicited e-mail was Beike Biotechnology, a China-based enterprise that claims to be able to treat cerebral palsy, autism, spinal cord injuries, optic nerve disorders and two dozen other conditions with stem cells. Scientists say the treatments rely on flawed theories, have not been vetted to tell if they will make any difference and amount to patients paying to be subjects of an experiment.

Just as scientists are critical of Beike's medical claims, marketing experts say the company uses questionable tactics, relying on patient testimonials that are difficult - if not impossible - to verify. It tries to lure customers by using emotional accounts from those who have the most at stake: Patients and their families who have often solicited the financial support of a community hungry for happy endings.

With its aggressive approach, Beike (pronounced Bay-Ka) has built itself into one of the largest stem cell companies in the world. It has done so by using the Internet to spread one unchecked "miracle" story after another, like a modern-day game of telephone. With each retelling, the stories and their alleged results get a little more fantastic.

As part of its examination of Beike, the Journal Sentinel built a database of all the patients listed on the company's Web site. Reporters contacted more than two dozen of them to see how they learned of Beike and what their experiences with the company were. The newspaper found:

• Unsolicited contact: The company's marketing agents troll the Internet looking for families desperate for cures and offer them unrealistic medical outcomes. In one case, a representative quoted a 98% improvement rate for an unproven treatment, which scientists call outrageous.

Alex Moffett, chief executive officer of Beike's holding company, said that recruiters' tactics and claims are "impossible to control" and that Beike "obviously cannot police all such activities."

• Inaccurate information: The company perpetuates inaccurate or unsubstantiated information about the treatments on its Web site by linking to scores of newspaper and TV stories. These emotional accounts often lack any substantiation from doctors or scientists. The stories then entice others to seek Beike's treatments. The company does not list unfavorable stories that challenge the effectiveness of its treatments.

• Hidden ties: Beike's marketing agents, also called "facilitators" or "medical liaisons," funnel patients into a sophisticated system that provides help in raising money, making travel arrangements to China, securing passports, even wiring money to China to pay for the treatment. Some company agents have exaggerated their expertise and offered confusing descriptions of their relationships to the company.

Nevertheless, hundreds of families - including several from Wisconsin - have each spent tens of thousands of dollars on these treatments in recent years, often defying their doctors' advice and eliminating their chance to participate in rigorous clinical trials in the United States.

"Plenty of companies use the Internet to find customers," said Susan Lederer, chairman of the department of medical history and bioethics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. "But it seems particularly sleazy to take advantage of those who are desperate. These are people who are under stress. They are especially vulnerable to this hucksterism."

Moffett defended his sales staff and said he had little control over how they seek clients.

"Our young international staff members are passionate about stem cell therapies," he wrote in an e-mail to the Journal Sentinel. "They are on the Internet many hours a day and have expressed personal comments and are involved in various levels of interaction with blogs and other forums for comment and discussion. Beike feels this is their right to communicate as they wish."

More than two years after Lasswell was contacted by Beike, her daughter's sight is improving on its own. But Lasswell remains angry at the solicitation from Ross-Vaden.

"It was gross the way that she fished the Internet looking for me," said Lasswell, of Oakland, Calif.

Although Ross-Vaden said in her overture to Lasswell that she could treat her daughter's condition, Ross-Vaden is not a doctor or research scientist. Ross-Vaden said she developed Beike's protocol for treating the disease, but company officials deny that.

She says she is a registered nurse, but will not say where she is licensed.

The Journal Sentinel interviewed Ross-Vaden last year at her home in suburban Chicago. She refused to provide key information, such as where she received her degree, and did not want the name of her community mentioned.

"I've been harassed and threatened too many times," she said.

Ross-Vaden said that when she solicited Lasswell in 2007, she was working for Beike as vice president of the company's foreign patient division and she regularly traveled to China to help set up and supervise the treatments.

But Moffett said Ross-Vaden was not an employee. Rather she was paid a commission for each patient she referred.

However, Ross-Vaden said she was paid a straight salary and declined Beike's offer of a commission for new patients.

"I didn't feel comfortable taking a percentage," she said.

Ross-Vaden said she quit the company in March 2009 because she wanted to try to have another baby. She continues to recommend Beike to people she meets on the online chat room she supervises from her house.

Ross-Vaden said she became interested in stem cell treatments when her son, Justin, was born with significant brain injuries and received stem cell treatments in Mexico. He died four years ago at the age of 2.

She said she found Lasswell by setting up a program on her computer that would alert her to any stories or blog entries about certain diseases. She was surprised to hear of Lasswell's criticism.

"I'm offering hope," Ross-Vaden said. "No one has to take it."

When a patient signs on to pay for treatments, Beike often assigns a facilitator, also known as a medical liaison.

The company sets up blogs for its patients and encourages them to write about their time in China so that others can see how the treatment is going.Once patients are home, Beike officials follow the blogs to ensure they provide a positive spin, according to some patients.

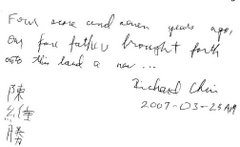

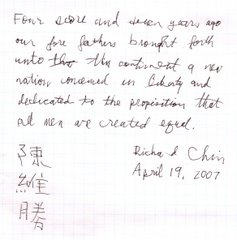

Richard Chin went to China in March 2007 for stem cell injections to treat ataxia, a disease of the nervous system.

Soon after he returned home, his wife wrote on their blog that Chin was scheduled to see his doctor for a post-treatment consultation. The blog also mentioned Chin had recently sprained his foot.

Three days before the scheduled doctor's appointment, the couple got an e-mail from Jon Hakim, then a Beike official, asking Chin to postpone the visit for another week.

Hakim referenced the foot injury and told them he wanted Chin to see the doctor on "an up day instead of a down day."

Chin's wife, Lilly Lock, was left feeling that Beike employees were monitoring what they wrote to affect the outcome of his medical examination.

"I cannot shake the feeling that Big Brother is watching," Lock wrote on the blog. "Is Jon using our blog to monitor us? I'd like to believe that he is interested in Richard's health as a friend and not as a salesperson of stem cell treatment. However, some of his requests can be construed as too self-serving."

Hakim also asked the couple to remove from their blog a link to a Wall Street Journal article that was critical of the company.

Hakim, who quit his job at Beike late last month, said he "asked nicely that they wait a little while" until Chin was feeling better.

"It's usually best to have the patient go in before and after evaluations in a similar state to get a real feel for the effects of the treatment."

Hakim said he left the company to take a job at a wireless start-up in China.

Beike markets itself aggressively on the Internet, such as with a flier that circulated before Christmas 2008:

"Join us in China to celebrate the holidays and we will wrap up 15 million little gifts to go under your tree for free! . . . Book to arrive in China and receive treatment in the month of December and you will receive a free stem cell transplant with approximately ten to fifteen million stem cells."

Smaller print explained: "certain restrictions do apply."

MEDIA ACCOUNTS

Many patients, though, find Beike through glowing stories in their local media.

Brandon Meinke of Janesville has Type 2 spinal muscular atrophy, a degenerative and potentially crippling disease. A relative sent his grandparents a story from Florida about a boy who had gone to Beike for stem cell treatments.

"We went on their Web site and saw all of these stories, and we felt like we had to try," said Sharon Vaughan, Brandon's grandmother.

In September 2008, a local TV station and the local newspaper ran stories on Brandon's upcoming trip. The newspaper story paraphrased a statement from Brandon's grandfather, Ron Martin: "There is no cure for Brandon's disorder, but other patients are proving the stem cell injections stop the progression."

Medical experts in spinal muscular atrophy say there is no such proof.

"I would argue there is absolutely no data to indicate cord blood will help with spinal muscular atrophy," said Stephen Minger, a British stem cell scientist who has studied the disease. "I can't imagine what it is that cord blood will do to help reverse that. . . . It is just ridiculous to believe that this is going to work."

When Kyle Knopes, a Janesville teenager with the same condition, read about Brandon, his hopes soared.

Kyle, now 17, was diagnosed as a baby with the condition. He had used a wheelchair since he was 18 months old. Conventional treatments weren't slowing the disease. By the time Kyle was 15, his neck muscles were too weak to support his head, and his fingers were starting to curl, making it difficult to hold a fork.

Kyle's doctor advised him and his family not to go, but by the following summer, in August 2009, Kyle and his mother and brother were off to China. They sent the company $27,500 and while they were in China, Kyle's father wired $3,500 for another injection. Kyle said he's greatly improved since he returned, having received eight injections of umbilical cord stem cells. He can hold his head up, grip a pen and even roll from side to side, something he said he hadn't been able to do in years.

But no doctor has measured Kyle's progress since he returned.

A handful of American doctors who have examined Beike patients before and after treatments for different conditions told the Journal Sentinel that they saw no change. In some cases, patients have reported fleeting improvements - and when they regress, Beike has used it as an opportunity to sell them another round of therapy.

Stem cell experts say the improvements patients report could be a placebo effect.

"Some patients report these kind of 'dramatic' improvements, but generally they don't last," said Minger, who is director of the stem cell biology lab at King's College in London.

Kyle said he doesn't care what other people think about whether these treatments work or not.

"I know what I could do before and what I can do now," he said. "It doesn't matter what people think or say about the treatments I got. How I feel is all that matters."

He now travels to schools around Janesville talking about the benefits of stem cell treatments, and stories about him are now among those promoted on Beike's Web site.

"I just had a woman from Canada call," Kyle said recently. "I think she's going to go."

Journalism ethics experts say reporters have to be careful not to play into the company's claims or they risk becoming unwitting barkers for an unproven product.

"Otherwise, we're back to the days of selling snake oil on the streets," said Stephen Ward, a professor of journalistic ethics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

"Studies show that the public makes medical decisions on what they see in the media," he said. "People who are sick want hope. They are ripe for being used. The chief journalistic rule is to be skeptical, check it out. A feel-good miracle story doesn't overcome a reporter's need to verify.

INTERNET SEARCH

Increasingly, people look to the Internet for health information, said Susannah Fox of the Pew Research Center in Washington, D.C. But many people aren't discriminating enough about the information they find there, she said.

The Internet is a source of power for people, particularly those who feel powerless against an incurable disease, Fox said.

"People facing medical crises want to become superheroes," she said. "They want to save a life. They believe the answer is out there if they can find it. "

Federal Trade Commission rules prohibit a company from making false claims on the Internet. But enforcement can be difficult when the company is based in another country, said Richard Cleland, an FTC spokesman.

He declined to say whether the FTC has had complaints about Beike.

Of all the cases that the Journal Sentinel reviewed, none got more public attention than that of Macie Morse.

The 16-year-old from northern Colorado went to China in the summer of 2008 for treatment of optic nerve hypoplasia.

She and her mother are claiming a miracle.

But the ophthalmologist who examined her before and after the treatments could find no improvement, said Macie's mother, Rochelle Morse. And experts in optic nerve hypoplasia said children with the condition often experience improved vision without any treatment at all.

Whatever the reason, Macie's eyesight has improved enough that she was granted a driver's permit last March.

However, the permit requires that she wear glasses specially fitted with a binocular-like device that allows her to see the lines on the road. In school, she requires a telescope to see the blackboard.

When Macie was featured on television news shows throughout Colorado after she got her driver's permit, she was not shown wearing the glasses and no mention was made of them.

"This is crazy!" Macie exclaims in one broadcast, as she drives the van down the street.

Shaun Boyd, a television reporter from Denver riding with her, says: "Crazy in a miracle-can-happen way."

Boyd, a reporter for CBS4 in Denver, said she didn't remember whether anyone told her Macie needed to wear the special glasses to drive.

"This is TV," Boyd said. "We drove around the block. It's not like I asked her not to wear the glasses so that we'd have a better shot or anything like that."

Rochelle Morse told the Journal Sentinel they weren't trying to fool viewers. She said Macie did not wear her glasses because it was only a short drive.

Beike officials said it should not be an issue.

"Regardless of why she was photographed like this, what a miracle for this child!" said Moffett. "It seems silly to try and find fault with such a wonderful outcome and the obviously life transformative benefits for her and the family."

Rochelle Morse organized an online chat room where she urges all who are considering it to go to China for the treatments. She also organizes medical awareness rallies to tout the benefits of the treatments.

At one such rally last year in Florida, Macie was the most anticipated speaker. She told the crowd that vision in one of her eyes has gone from 20/400 to 20/80.

"I saw snow fall for the first time," she told the crowd.

When asked to document Macie's improvement, Beike officials offered months ago to provide the Journal Sentinel with her medical records. They have not done so despite repeated requests.

Beike has compensated Macie's family for such testimonials with free transportation around China - a fact not mentioned at the rally.

Having spent $30,000 the first time, the family is getting ready to go back sometime this month for more treatment, hoping for still more improvement.

Rochelle Morse said in an interview she will ask the company for a discount for their upcoming trip for more treatments because of all the publicity the family has generated for the company.

At the rally, she had a message for the skeptics.

"It's not the placebo effect," she said, "and if it is, screw them. It works."

HOW UNVERIFIED CLAIMS ARE SPREAD

• Ron Martin, whose grandson, Brandon, suffers from Type 2 spinal muscular atrophy, gets a story from a Florida newspaper about a patient with the same disease who went to China for Beike's stem cell treatments. They, too, plan a trip to China.

• In September 2008, the local newspaper runs a story on Brandon's trip to China for the treatments, quoting Martin that stem cells are proving to stop the disease. Local TV stations also do stories.

• Kyle Knopes, who has the same disease, reads the story and calls Martin for more information. He plans a trip, too.

• The company, trading on the credibility of the media outlets, posts the stories on its Web site.

RALLYING CRY

In March 2009, a Journal Sentinel reporter attended a stem cell awareness rally in Punta Gorda, Fla., organized by a supporter of Beike Biotechnology.

The event, held in a gazebo overlooking Charlotte Harbor, brought together both prospective and former patients, including children who had received treatment from Beike for optic nerve hypoplasia. About 75 people attended.

Those in the crowd included Beike officials and others, purporting to be independent, whose actual roles and relationships to the company were not made clear. One example:

One of the speakers was Ali A. Hakim, introduced as an expert in stem cells.

Hakim, 82, a urologist who lives in Minnesota, is the father of Jon Hakim, then Beike's marketing director.

Ali Hakim gave a talk praising the company's work, but was vague when asked about his relationship to the company: "I have been working with them for four years. I don't work for them. I don't take one penny."

However, the event's organizer, Carol Petersen, whose grandson was treated by Beike, described herself as a salaried employee of Ali Hakim.

"He's part of them," she said of Hakim, "but I wouldn't call him a Beike employee."

Mark Johnson, the reporter from the Journal-Sentinel, who contacted us in January of this year for this article wrote the first part of this series here.

Friday, May 28, 2010

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)